Publication Date: October 1, 2025

Publication Date: October 1, 2025

Author: Dr. Evelyn Monroe (Cognitive Epistemology)

Supervised by: The Anonymous Architect

I. The Earliest Forms of Banking Practices

The origins of banking date back more than three thousand years. In Mesopotamia, temples and palaces already kept records of grain, silver, and debt receipts. Babylonian priests accepted “long money” — stored grain and metals — issuing written notes that began to function as a form of currency. In ancient Greece and Rome, the first moneylenders and trapezitai appeared, not only exchanging coins but also accepting deposits with interest. Thus, from the very beginning, a bank served as an intermediary of storage and trust.

II. Medieval Europe

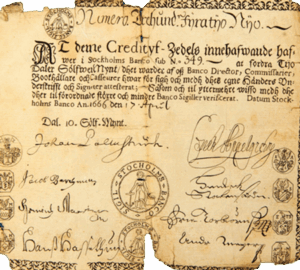

Italy. In the 12th–14th centuries, at the great fairs of Northern Italy, banchieri (moneychangers) operated from benches — giving us the very word “bank.” In 1472, the Monte dei Paschi di Siena was founded in Siena, the oldest bank still in operation today. Its initial purpose was to provide credit to farmers and merchants.

France. In Paris, 1716 saw the creation of the Banque Générale, which later became the Banque de France. Its mission was to support the royal treasury and regulate the circulation of banknotes.

The Netherlands. In 1609, the Amsterdam Wisselbank was established. It became a model of financial reliability, serving international trade and pioneering cashless payments through book transfers.

Germany. In the 17th century, the banks of Hamburg and Nuremberg emerged, focused on maintaining stable currency and providing credit to merchants.

Spain and Portugal. Here, banking was tightly bound to colonial expansion: the Casa de Contratación in Seville and subsequent financial institutions managed the flow of silver and gold from the Americas, funding both maritime expeditions and wars.

Transitional Emphasis

Temple priests, Italian merchants, royal financiers — they all held in their hands not only money but also trust. Yet this trust always carried an external seal: the mark of a king, the cross of a temple, the guild’s emblem on a promissory note. Even the Monte dei Paschi di Siena, founded as a pillar of support for farmers and traders, eventually transformed into an ordinary commercial bank, where profit replaced trust as the primary measure.

COSMIC Commentary

For thousands of years, the bank remained a space of trust — from the Sumerian temple to the Amsterdam trading hall. Yet this trust was always externalized: it always required an intermediary, a seal, an authority.

COSMIC proposes a different principle: a distinction recorded by the subject itself needs no intermediary. A form disconnected from execution is beyond external verification. Where meaning is internally sustained, both the keeper and the guarantor become unnecessary.